Forging your clean energy future

Who We Are

We use profits from innovative energy ventures to make the renewable revolution accessible for all.

Citizens Energy Corporation was founded by former U.S. Rep. Joseph P. Kennedy II in 1979 to make life's basic needs more affordable. In the past 44 years, we have provided over $600 million in charitable benefits through our profits from dozens of successful businesses.

Learn moreCharitable Programs

From heating shelters to lowering the price of subscription medication, we reinvest in our global host communities to make sure no one is left out in the cold.

Our Industries

We own and operate solar, battery storage, microgrid and transmission projects from coast to coast.

Latest Updates

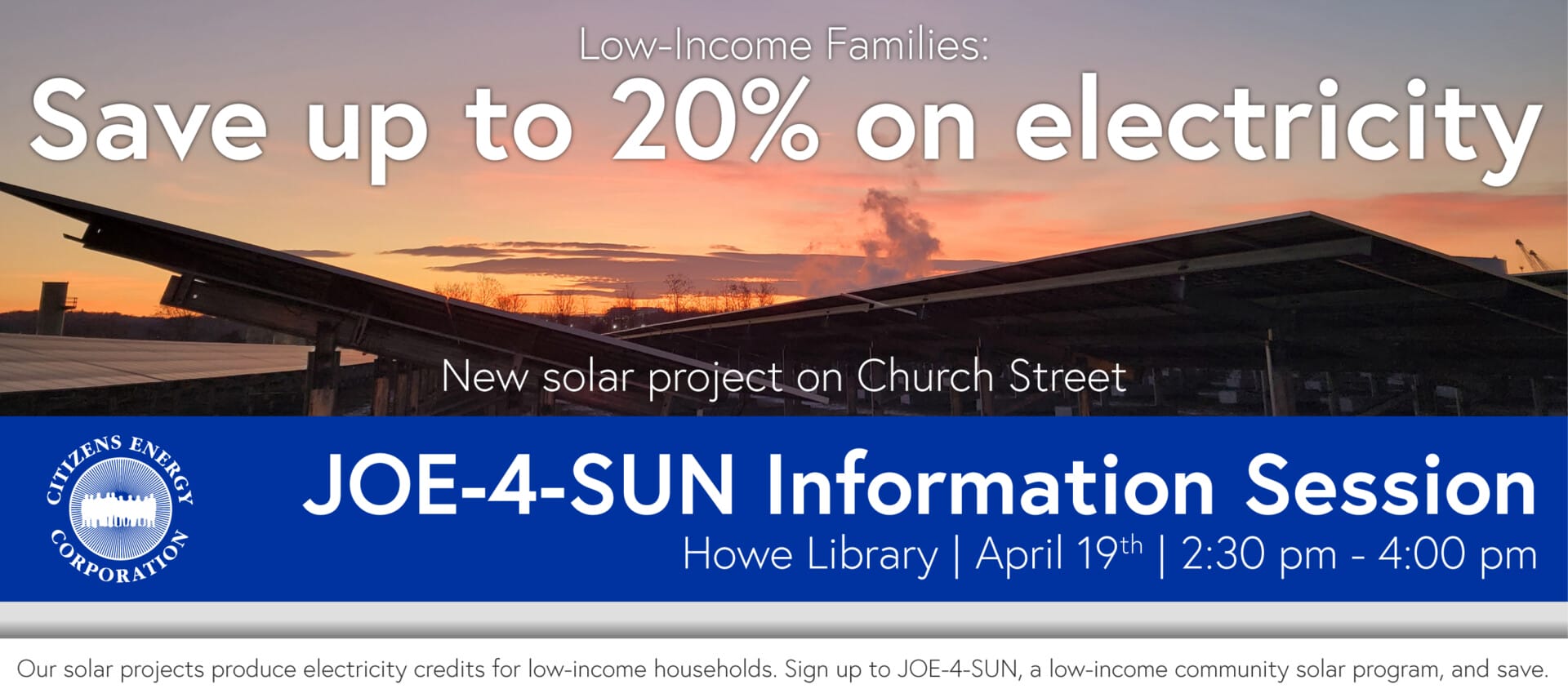

Join Citizens Energy in Albany to Learn About Electric Savings

Read more

PG&E aims to raise up to $1B for transmission through leases to Citizens Energy

Read more

PG&E, Citizens Energy Partnership Would Accelerate Essential Grid Work for Customers and Fund Energy-Related Charitable Programs

Read more

IID announces $100,000 in financial assistance for Niland residents affected by unprecedented 2023 flood

Read more